Off-Label Drug Use Checker

Check if Your Medication is Off-Label

Results

5 Key Questions to Ask Your Doctor

- Is this approved for my condition? If not, why are you recommending it?

- What evidence supports this? Is it from a study or just a few cases?

- What are the risks I might not have heard about?

- Will my insurance cover this? If not, how much will I pay?

- Are there any approved alternatives?

Insurance Coverage

Many insurers require proof from NCCN or DRUGDEX compendia. Without approval, you may face $5,000+ bills.

Risk Level

Every year, millions of Americans take medications that weren’t originally approved by the FDA for their condition. A child with autism might get an antipsychotic for irritability. A cancer patient might receive a drug approved for lung cancer to treat a rare sarcoma. An adult with severe depression might be given a medication approved for epilepsy. These aren’t mistakes. They’re common, legal, and often life-saving - but they come with risks most people don’t know about.

What Exactly Is Off-Label Drug Use?

Off-label drug use means prescribing a medication for a purpose, dosage, age group, or route that hasn’t been officially approved by the FDA. The drug itself is approved - just not for that specific use. For example, metformin is approved for type 2 diabetes, but doctors often prescribe it for prediabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or even weight loss. That’s off-label. So is giving benzodiazepines to infants for seizures, even though they’re only approved for adults. Or using doxycycline as a long-term anti-inflammatory for rheumatoid arthritis, even though it’s labeled only for infections.

The FDA approves drugs based on clinical trials that prove safety and effectiveness for a specific use. But once a drug hits the market, the agency doesn’t control how doctors prescribe it. That’s because the FDA regulates drugs, not medical practice. A 1996 court case confirmed this: off-label prescribing is a matter of medical judgment. And it’s everywhere. Up to 20% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are off-label. In pediatrics, it’s 62%. In oncology, it’s 85%.

Why Do Doctors Do It?

Simple: because patients need options.

Many diseases - especially rare cancers, neurological disorders, or childhood conditions - don’t have FDA-approved treatments. Clinical trials take years and cost tens of millions of dollars. Pharmaceutical companies won’t spend that money if the market is small. So doctors turn to existing drugs with promising evidence.

Take methotrexate. It was approved for cancer and psoriasis. But doctors discovered it suppresses immune activity. Now it’s a go-to for rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and even severe eczema - none of which are on the label. In pediatric oncology, doctors use vincristine at higher frequencies than approved because studies show better survival rates for certain tumors. In psychiatry, olanzapine is routinely prescribed for insomnia or anxiety, even though it’s only approved for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Off-label use fills gaps where no other options exist. Without it, thousands of patients would get no treatment at all.

The Dark Side: When Off-Label Use Goes Wrong

But not all off-label use is smart. Some is based on weak evidence - or worse, marketing.

The most infamous example is Fen-Phen. Fenfluramine and phentermine were both approved for weight loss individually. But when doctors combined them off-label, they saw dramatic results. The problem? No one studied the combo properly. Years later, thousands of patients developed fatal heart valve damage. The drugs were pulled from the market. The lesson? Just because something works in a few patients doesn’t mean it’s safe for everyone.

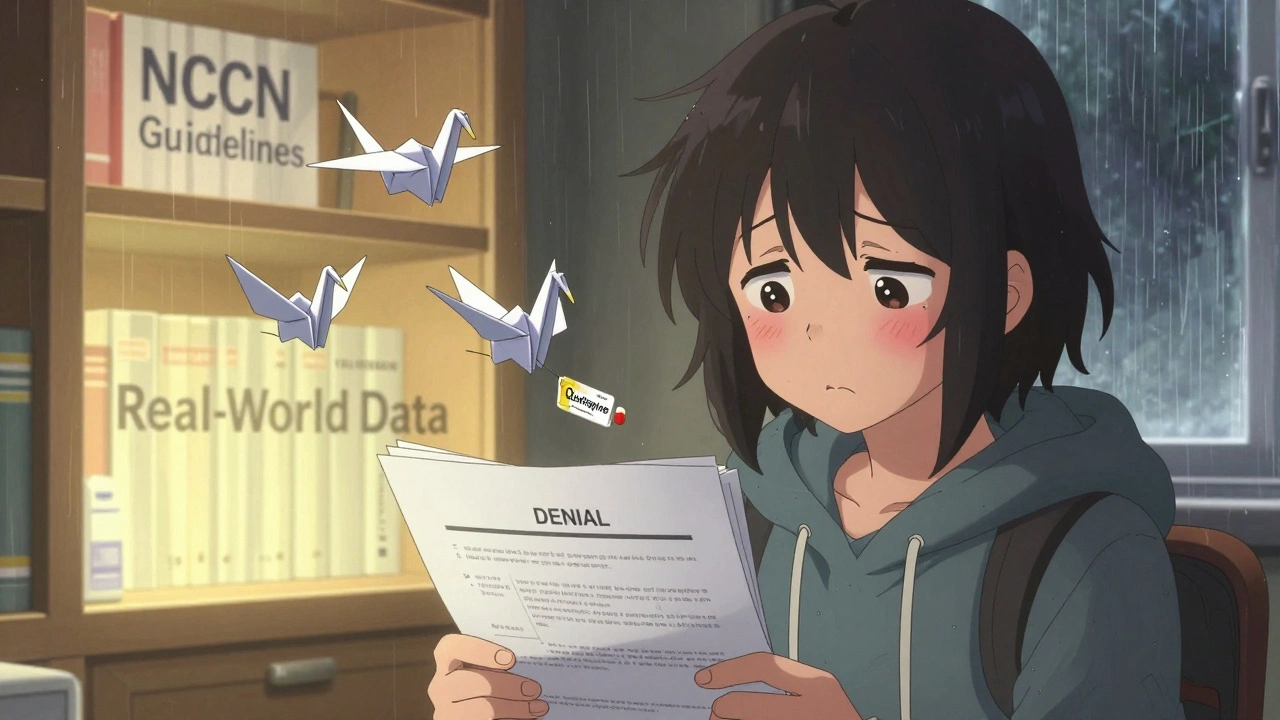

Another risk: side effects you didn’t expect. A patient prescribed quetiapine (an antipsychotic) off-label for sleep might gain 30 pounds, develop high blood sugar, or suffer tremors - side effects rarely discussed because they weren’t studied in sleep trials. Insurance won’t cover it, either. Many insurers require proof from recognized compendia like the NCCN or DRUGDEX before paying for off-label drugs.

And then there’s the marketing problem. In 2012, GlaxoSmithKline paid $3 billion to settle charges for illegally promoting off-label uses of drugs like paroxetine for kids and epilepsy drugs for bipolar disorder. Pharmaceutical companies are forbidden from promoting off-label uses - but doctors aren’t. That creates a gray zone where sales reps whisper suggestions, and doctors hear what they want to hear.

How Do Doctors Decide What’s Safe?

Not every off-label use is equal. Some are backed by decades of research. Others are based on a single case report.

Top doctors rely on four things:

- Published studies - especially randomized trials and systematic reviews.

- Professional guidelines - like the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) compendium, which lists off-label cancer drugs Medicare will cover.

- Expert consensus - what experienced specialists agree on.

- Real-world data - outcomes from electronic health records and patient registries.

For example, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is used off-label for rare autoimmune diseases. One patient in the New England Journal of Medicine survived a life-threatening condition only after IVIG was tried - but it took three months of insurance appeals to get approval. That’s the reality: even when it works, the system fights it.

Doctors spend an average of 27 minutes per patient researching off-label uses. That’s time they could spend with patients. And 45% say prior authorization adds 3 to 5 days to treatment. That delay can be deadly in cancer or sepsis.

Who Pays for Off-Label Drugs?

Insurance companies don’t like off-label prescriptions. They see them as risky and expensive. Most require:

- Proof the use is listed in NCCN, DRUGDEX, or similar compendia.

- Documentation that other approved treatments failed.

- Pre-approval from the insurer.

If you’re prescribed an off-label drug, you might get hit with a $5,000 bill. That’s why many patients give up. A 2022 UnitedHealthcare policy states that coverage depends on whether the use is "medically appropriate and supported by strong evidence." But what’s "strong"? That’s up to the insurer - and often, it’s not enough.

The Future: Will Off-Label Use Ever Go Away?

Probably not. And that’s not a bad thing.

The FDA is starting to catch up. The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 lets drug makers use real-world data - like patient records and registries - to apply for new label approvals. That means drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic), which is now widely used off-label for weight loss, might get official approval for obesity soon. That’s progress.

But innovation won’t stop. Rare diseases, pediatric cancers, and complex mental illnesses will always outpace drug approvals. As long as that’s true, doctors will keep prescribing off-label.

The goal isn’t to ban off-label use. It’s to make it smarter. Better evidence. Faster approvals. Clearer guidelines. And less guesswork for patients.

Right now, off-label prescribing is a patchwork of science, necessity, and luck. It saves lives. It harms some. It’s messy. But in medicine, the best solutions rarely come from a checklist. They come from judgment - and sometimes, from daring to use a tool in a way it wasn’t designed for.

What Patients Should Know

If your doctor prescribes a drug off-label:

- Ask: "Is this approved for my condition? If not, why are you recommending it?"

- Ask: "What evidence supports this? Is it from a study, or just a few cases?"

- Ask: "What are the risks I might not have heard about?"

- Ask: "Will my insurance cover this? If not, how much will I pay?"

- Ask: "Are there any approved alternatives?"

Don’t be afraid to push for answers. Off-label doesn’t mean unsafe - but it does mean you need to be informed.