When a generic drug hits the market, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators make sure it does? Traditional bioequivalence tests look at two numbers: the highest concentration of drug in the blood (Cmax) and the total exposure over time (AUC). For many drugs, that’s enough. But for others-especially extended-release pills, abuse-deterrent opioids, or combination formulations-those two numbers miss the real story. That’s where partial AUC comes in.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

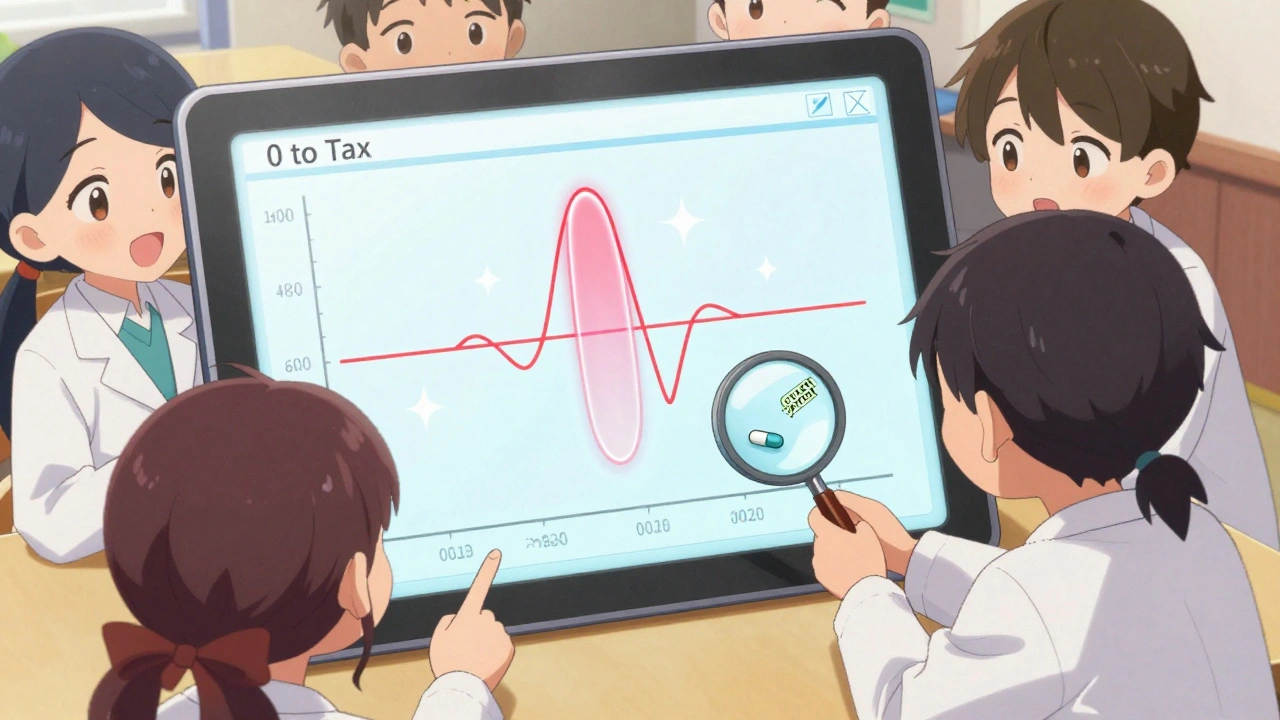

Think of a drug’s concentration in your blood as a curve over time. The total AUC measures the area under that entire curve. Cmax tells you the peak. But what if two drugs have the same total exposure and same peak-but one releases the drug too fast at the start, and the other too slow? You could end up with one drug causing side effects early, and the other not working until hours later. That’s not bioequivalent in practice, even if the numbers say it is. This problem became obvious with prolonged-release formulations. In the early 2010s, regulators noticed that some generic versions passed standard bioequivalence tests but still caused clinical issues. A 2014 study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generics that met traditional criteria failed to match the reference product’s absorption pattern when analyzed with partial AUC. In fed and fasting studies combined, that failure rate jumped to 40%. The numbers weren’t lying-they just weren’t telling the whole truth.What Is Partial AUC?

Partial AUC, or pAUC, is a pharmacokinetic tool that zooms in on a specific time window during the drug’s absorption phase. Instead of looking at the whole curve, it calculates the area under the curve only between two defined time points-like from 0 to 2 hours, or from the start of absorption until the reference product’s peak concentration. The key idea is simple: focus on the part of the curve that matters most for how the drug works. For a painkiller, you care about how quickly it relieves pain-that’s usually within the first hour or two. For a long-acting blood pressure med, you care that levels stay steady after the initial rise. pAUC lets regulators measure those critical windows directly. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) both started pushing for pAUC around 2013. The EMA’s draft guideline was the first to formally recognize it as a necessary tool for modified-release products. The FDA followed, and by 2018, its Center for Drug Evaluation and Research began standardizing how pAUC should be calculated across all drug types.How Is Partial AUC Calculated?

There’s no single way to define the time window for pAUC. The FDA says it should be tied to a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effect-meaning, when does the drug start working in the body? But in practice, regulators use three common approaches:- Time-based cutoff: e.g., AUC from 0 to 1.5 hours

- Tmax-based cutoff: e.g., AUC from 0 to the time when the reference product reaches its peak concentration

- Cmax-based cutoff: e.g., AUC from 0 to the time when concentration drops to 50% of Cmax

When Is Partial AUC Required?

pAUC isn’t needed for every drug. But it’s becoming mandatory for certain categories:- Extended-release formulations (e.g., metformin ER, oxycodone ER)

- Abuse-deterrent opioids (FDA now requires pAUC in over 20 product-specific guidances)

- Mixed-mode products (e.g., a pill with both immediate- and extended-release layers)

- Drugs with narrow therapeutic windows (like warfarin or lithium)

- CNS drugs (antidepressants, antiepileptics) where timing affects efficacy

- Central nervous system drugs: 68% of new submissions

- Pain management: 62%

- Cardiovascular agents: 45%

Real-World Impact: Successes and Failures

pAUC has stopped unsafe generics from reaching patients. A case study presented at the 2021 AAPS meeting showed a generic version of an extended-release stimulant passed traditional bioequivalence tests. But when analyzed with pAUC, it had 22% less exposure in the first hour. That meant patients might not get enough drug early in the day, leading to poor symptom control. The product was pulled before approval. On the flip side, implementing pAUC adds cost and complexity. A biostatistician at Teva reported that for one extended-release opioid generic, the study size had to increase from 36 to 50 subjects. That added $350,000 to development costs. But they avoided a clinical failure down the line. Still, many generic companies struggle with inconsistency. FDA inspection reports from 2022 show 17 ANDA submissions were rejected because the pAUC time window was poorly defined. Only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances clearly explain how to pick the cutoff time. That leaves developers guessing-and sometimes failing.

What Skills Do You Need to Work With pAUC?

If you’re in pharma R&D or bioequivalence testing, pAUC is no longer optional. Job postings for bioequivalence specialists now list pAUC expertise as a requirement in 87% of cases (BioSpace, 2023). You need to know:- How to define clinically meaningful time windows

- How to use software like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM for pharmacokinetic modeling

- How to apply the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller method to calculate confidence intervals for pAUC ratios

- How to justify your time window choice to regulators

The Future of Partial AUC

The trend is clear: pAUC is becoming standard for complex drugs. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC analysis-up from 35% in 2022. The FDA is working on solutions to the biggest problem: inconsistency. In early 2023, they launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC time windows based on historical reference product data. The goal? Reduce ambiguity, cut development time, and make approvals faster and fairer. But challenges remain. The International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development found that inconsistent pAUC rules across the U.S., Europe, and other regions add 12-18 months to global drug development timelines. Harmonization is the next frontier.Final Thoughts

Partial AUC isn’t just another statistic. It’s a smarter way to ensure that a generic drug doesn’t just match the brand on paper-it matches in real life. For patients relying on extended-release medications, abuse-deterrent opioids, or CNS drugs, this isn’t academic. It’s about safety, effectiveness, and trust. The science behind pAUC is solid. The regulatory push is real. And the industry is adapting, even if it’s slow and expensive. If you’re working in generic drug development, bioequivalence testing, or pharmacokinetics, understanding pAUC isn’t optional anymore. It’s the new baseline.What is the difference between total AUC and partial AUC?

Total AUC measures the entire drug exposure from the moment it enters the bloodstream until it’s fully cleared. Partial AUC (pAUC) measures exposure only during a specific, clinically relevant time window-like the first 2 hours after dosing. While total AUC tells you how much drug you got overall, pAUC tells you how fast or when you got it, which matters more for some drugs.

Why is partial AUC used for abuse-deterrent opioids?

Abuse-deterrent formulations are designed to slow down drug release if someone tries to crush or snort the pill. If a generic version releases the drug too quickly in the first hour, it could still be abused. pAUC measures exposure during that critical early window to make sure the generic matches the brand’s abuse-deterrent performance.

Does partial AUC replace Cmax and total AUC?

No. pAUC is an additional metric, not a replacement. Regulators still require Cmax and total AUC for most drugs. But for complex formulations-like extended-release or mixed-mode products-pAUC adds critical information that the other two metrics can’t provide.

How do regulators decide the time window for partial AUC?

The FDA recommends linking the time window to a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effect-like when the drug starts working. In practice, they often use the reference product’s Tmax (time to peak concentration) or a fixed time interval like 0-2 hours. Product-specific guidances should specify the window, but many lack clarity, leading to confusion among developers.

Why is partial AUC more variable than total AUC?

Because pAUC focuses on a narrow time window, small differences in absorption timing between subjects have a bigger impact. If one person absorbs the drug 30 minutes faster than another, that difference is magnified in a 0-1.5-hour window but smoothed out over 24 hours. Higher variability means larger study sizes are needed to detect equivalence reliably.