Thyroid cancer is one of the fastest-growing cancer diagnoses in the U.S., with over 44,000 new cases each year. But here’s the surprising part: most people diagnosed with it will live a normal lifespan. That’s because the most common types are slow-growing, highly treatable, and often caught early. The real challenge isn’t just surviving-it’s navigating the treatment choices: thyroid cancer types, radioactive iodine therapy, and thyroidectomy. Each decision affects your long-term health, quality of life, and even how you feel day to day.

What Are the Main Types of Thyroid Cancer?

Not all thyroid cancers are the same. They’re named after the cells they come from, and that determines how they behave and how they’re treated.Papillary thyroid carcinoma makes up 70-80% of cases. It grows slowly, often spreads to nearby lymph nodes, but responds extremely well to treatment. If you’re under 45 and have a small papillary tumor, your 10-year survival rate is over 98%.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma accounts for 10-15%. It’s more likely to spread through the bloodstream to distant organs like the lungs or bones, but it still has a high cure rate when caught early.

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is rare-only 3-5% of cases. It starts in the C-cells that make calcitonin. Some cases are inherited, linked to genetic syndromes like MEN2. Unlike papillary and follicular types, MTC doesn’t absorb iodine, so radioactive iodine won’t work.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is the most aggressive. Less than 2% of cases, but it grows fast, spreads quickly, and is often diagnosed at stage IV. Survival drops sharply without immediate, aggressive treatment. It doesn’t respond to radioactive iodine or most standard therapies.

Why Radioactive Iodine Therapy Is Used-And When It’s Not

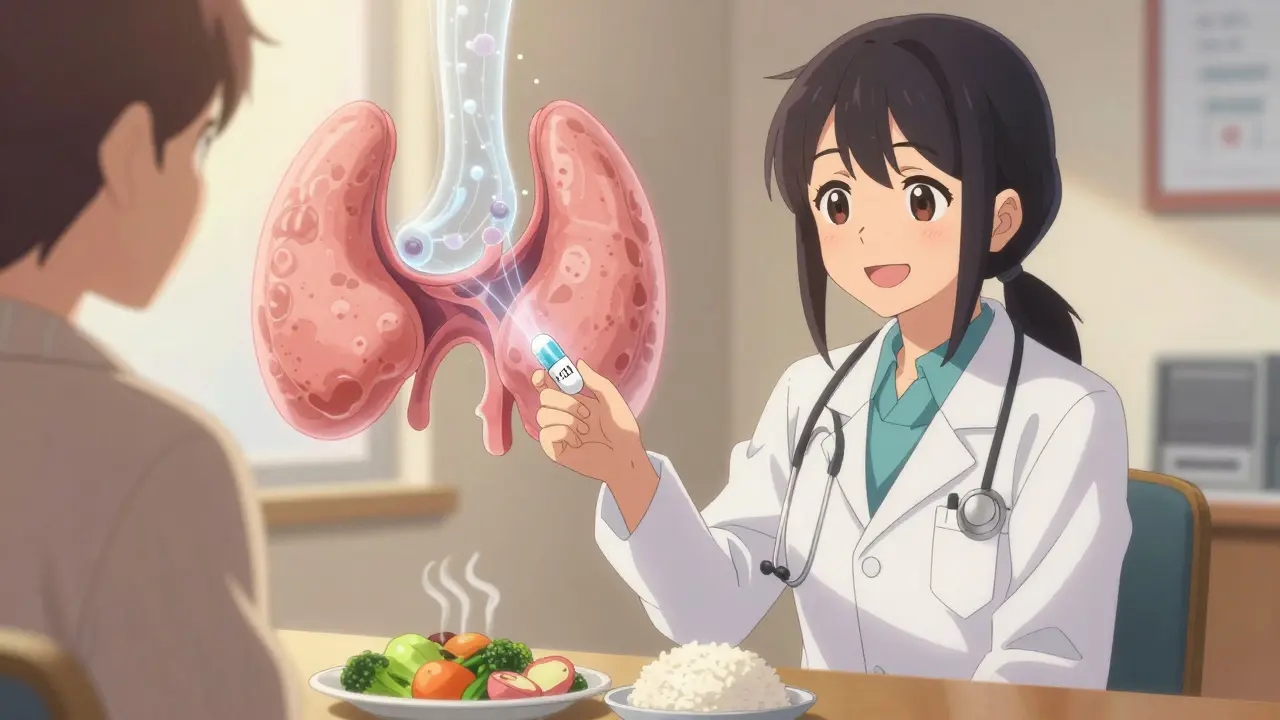

Radioactive iodine (I-131) has been used since the 1940s and remains a key tool for treating differentiated thyroid cancers-papillary and follicular. The thyroid is the only organ in the body that absorbs iodine. That’s the trick: you swallow a capsule or liquid containing I-131, and it travels through your bloodstream, seeking out any remaining thyroid tissue or cancer cells that still absorb iodine.It’s used for two main reasons: to destroy leftover thyroid tissue after surgery (called remnant ablation) and to treat cancer that has spread to lymph nodes or distant sites like the lungs.

But here’s what many don’t realize: not everyone needs it. For small, low-risk papillary cancers-especially under 1 cm and without aggressive features-the 2015 American Thyroid Association guidelines say RAI isn’t necessary. Studies like the HiLo trial showed no difference in outcomes between a 30 mCi dose and a 100 mCi dose for ablation. Lower doses mean less radiation exposure, fewer side effects, and lower cost.

RAI doesn’t work on medullary or anaplastic cancers because those cells don’t have the iodine pump. For those, surgery, external beam radiation, or targeted drugs like selpercatinib (for RET mutations) or dabrafenib/trametinib (for BRAF mutations) are used instead.

Preparing for RAI is tough. You either stop taking thyroid hormone for 2-4 weeks (which causes fatigue, brain fog, weight gain, and depression) or get injections of recombinant TSH (Thyrogen®), which avoids hypothyroidism but costs more. Many patients say the low-iodine diet is harder than the surgery. No dairy, eggs, seafood, bread with iodized salt, or even some medications. It’s a strict, isolating regimen.

Thyroidectomy: What’s Removed, and How

Surgery is the first step for almost all thyroid cancers. The type of surgery depends on the cancer’s size, type, and spread.Lobectomy removes just one lobe of the thyroid. It’s often enough for small, low-risk papillary cancers. Recovery is quick-many go home the same day. But if cancer is found later to be more aggressive, a second surgery (completion thyroidectomy) may be needed.

Total thyroidectomy removes the entire gland. This is standard for larger tumors, cancers that have spread to lymph nodes, or if RAI is planned. It’s a 2-3 hour surgery with a 6-8 cm incision. Most patients stay one or two nights.

Modern techniques focus on protecting two critical structures: the recurrent laryngeal nerves (which control your voice) and the parathyroid glands (which regulate calcium). Surgeons use nerve monitoring during surgery, which cuts the risk of voice changes from over 12% down to under 5% after 25-30 procedures.

Some newer approaches-like transoral (through the mouth) or robotic surgery-promise no visible scar. But studies show they have higher complication rates than traditional open surgery. For most patients, the open approach is still the safest and most reliable.

Life After Surgery and RAI

After a total thyroidectomy, you’ll need lifelong thyroid hormone replacement-usually levothyroxine. But here’s the catch: many people still feel off. In surveys, 68% of thyroid cancer survivors report ongoing symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, or muscle weakness-even when their TSH levels are “normal.”Doctors typically aim for a TSH level between 0.5 and 2.0 mIU/L for intermediate-risk patients. For higher-risk cases, they may suppress TSH even lower, to below 0.1, to reduce cancer recurrence risk. But that can strain the heart and bones over time.

Low calcium is another common issue. If the parathyroid glands are damaged or removed during surgery, you may need calcium and vitamin D supplements long-term. About 22% of patients develop permanent hypoparathyroidism.

Voice changes are also common. Some are temporary, caused by swelling. Others are permanent, especially if nerves were stretched or injured. Many patients adapt, but speech therapy can help.

Follow-up care includes regular blood tests (TSH, thyroglobulin), neck ultrasounds, and sometimes whole-body scans after RAI. Most people return to normal life within 4-6 weeks. Driving is restricted for 7-10 days after surgery, and heavy lifting is avoided for 3 weeks.

What’s New in Thyroid Cancer Treatment?

The field is shifting away from one-size-fits-all treatment. For small, low-risk papillary cancers, active surveillance is now an option. In Japan, where this is common, only 3.8% of microcarcinomas (<1 cm) grew over 10 years. Many U.S. doctors now recommend monitoring instead of immediate surgery for these cases.Targeted drugs are changing the game for advanced cases. Selpercatinib and pralsetinib work for RET-mutant medullary cancer. Dabrafenib and trametinib help BRAF-mutant anaplastic cancer-boosting median survival from 5 to over 10 months.

Researchers are also testing drugs that can make resistant cancers absorb iodine again. Selumetinib, for example, restored RAI uptake in over half of patients in a 2022 trial. If this works on a larger scale, it could bring new hope to those who’ve run out of options.

And while surgery and RAI remain standard, the trend is clear: less is often more. Up to 30% of patients with papillary thyroid cancer get more treatment than they need-unnecessary surgery, unnecessary RAI, unnecessary lifelong medication. The goal now is precision: treating aggressively when needed, and holding back when it’s safe.

What to Ask Your Doctor

If you’re facing a thyroid cancer diagnosis, these questions matter:- What type and stage is my cancer?

- Do I really need a total thyroidectomy, or could a lobectomy be enough?

- Will I need radioactive iodine? Why or why not?

- What are the risks to my voice and calcium levels?

- Will I need lifelong medication? What’s the target TSH level for me?

- Are there genetic factors I should test for?

- Can I get a second opinion from a thyroid cancer specialist?

Don’t rush. Take time. Ask for the latest guidelines. Bring someone with you to appointments. Thyroid cancer is one of the few cancers where you have time to make thoughtful choices-and those choices shape your life for decades.

Is radioactive iodine therapy always necessary after thyroid surgery?

No. For low-risk papillary thyroid cancer-especially tumors under 1 cm with no spread or aggressive features-radioactive iodine is often not needed. Guidelines from the American Thyroid Association now recommend against routine RAI in these cases. Studies show no survival benefit, and lower doses or no RAI reduce side effects and radiation exposure. The decision should be based on tumor size, type, lymph node involvement, and molecular markers-not just the fact that surgery was done.

Can thyroid cancer come back after treatment?

Yes, but recurrence is uncommon for low-risk cases. Papillary and follicular thyroid cancers have a 90%+ long-term survival rate. Recurrence most often happens in lymph nodes in the neck and can be treated with another surgery or RAI. Blood tests for thyroglobulin (a protein made by thyroid cells) are the best way to monitor for recurrence. If thyroglobulin rises over time, it signals cancer may be returning-even before imaging shows it.

Why do I feel so tired after thyroid cancer treatment?

Fatigue is common after thyroid cancer treatment for several reasons. After surgery and RAI, your body is adjusting to life without natural thyroid hormone. Even with levothyroxine, many people don’t feel completely normal-42% of patients report brain fog as their top symptom. RAI preparation (thyroid hormone withdrawal) causes hypothyroidism, which leads to extreme tiredness, weight gain, and depression. Some people also have lingering low calcium or vitamin D levels, which worsen fatigue. It’s not just in your head-your metabolism is resetting.

Are there alternatives to surgery for thyroid cancer?

For most thyroid cancers, surgery is the standard because it’s the most effective way to remove the tumor. But for very small, low-risk papillary microcarcinomas (<1 cm), active surveillance is a valid alternative. You get regular ultrasounds and blood tests, and surgery is only done if the tumor grows. This approach is common in Japan and increasingly accepted in the U.S. for patients who prefer to avoid surgery. Radiofrequency ablation is being studied but is not yet standard care for cancer-only for benign nodules.

How long does recovery take after a thyroidectomy?

Most people return to light activities within a week. Driving is usually restricted for 7-10 days after surgery. Heavy lifting and strenuous exercise should be avoided for 3 weeks. Hospital stays are typically 1-2 days for total thyroidectomy and same-day for lobectomy. Full recovery-feeling like yourself again-can take 4-6 weeks. Voice changes or neck stiffness may linger longer. Long-term recovery means adjusting to lifelong thyroid hormone replacement and managing potential calcium issues.

Can thyroid cancer be inherited?

Most thyroid cancers are not inherited. But about 5-10% of medullary thyroid cancers are linked to genetic syndromes like MEN2A or MEN2B, caused by RET gene mutations. If you have medullary cancer, especially if you’re under 40 or have a family history, genetic testing is recommended. Papillary and follicular cancers rarely run in families, though some rare inherited conditions (like Cowden syndrome) can increase risk. Genetic counseling is advised if multiple family members have thyroid cancer or related tumors.