Hypokalemia Risk Calculator

When you’re managing heart failure, diuretics are often the first line of defense against fluid buildup. But there’s a hidden risk that many patients and even some providers overlook: hypokalemia. Low potassium isn’t just a lab value-it’s a silent trigger for dangerous heart rhythms, hospital readmissions, and even sudden death. If you or someone you care for is on diuretics like furosemide, bumetanide, or torsemide, understanding how to prevent and treat low potassium isn’t optional. It’s essential.

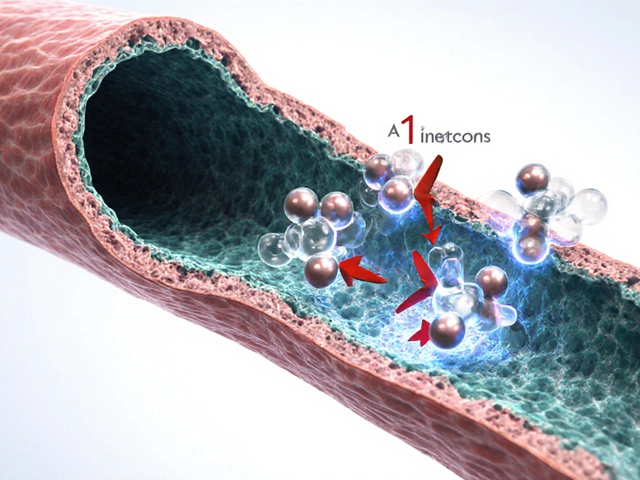

Why Diuretics Cause Low Potassium

Loop diuretics work by blocking salt reabsorption in the kidneys, which pulls water out of the body. But that same mechanism also flushes out potassium. Every time you pee out extra sodium, your kidneys compensate by dumping more potassium into the urine. This is normal physiology-but in heart failure patients, it becomes dangerous. Studies show that 20-30% of heart failure patients on loop diuretics develop hypokalemia (serum potassium below 3.5 mmol/L). The risk climbs higher with larger doses, older age, kidney problems, or when diuretics are combined with other potassium-wasting drugs like thiazides or laxatives. Even worse, the body doesn’t respond the same way every day. Diuretic tolerance builds up over time, meaning the same dose becomes less effective at removing fluid-but still keeps flushing potassium. That’s why some patients feel better after a dose, then crash hours later with muscle cramps or palpitations.The Real Danger: Arrhythmias and Death

Low potassium doesn’t just cause weakness or fatigue. In a heart already weakened by failure, it can trigger life-threatening arrhythmias like ventricular tachycardia or torsades de pointes. Research shows that when potassium drops below 3.5 mmol/L, the risk of death increases by 1.5 to 2 times. This isn’t theoretical. It’s backed by decades of clinical data, including the RALES trial, which found that patients with advanced heart failure who took spironolactone (a potassium-sparing drug) had a 30% lower risk of dying-not just because of better fluid control, but because their potassium stayed in a safer range. The target? Keep potassium between 3.5 and 5.5 mmol/L. Not too low. Not too high. Just right. Going above 5.5 mmol/L can be dangerous too, especially if you’re on ACE inhibitors or MRAs. But staying below 3.5 mmol/L is far more immediately risky.How to Fix It: Potassium Replacement and Medication Adjustments

If your potassium is mildly low (3.0-3.5 mmol/L), oral potassium chloride is usually enough. A typical dose is 20-40 mmol per day, split into two doses to avoid stomach upset. Don’t just grab over-the-counter potassium pills-they often contain only 99 mg (about 2.5 mmol), which is nowhere near enough. Prescription potassium chloride tablets or liquid are needed for real correction. If potassium drops below 3.0 mmol/L, or if you’re having symptoms like irregular heartbeat, dizziness, or severe muscle weakness, you’ll likely need IV potassium in a hospital setting. This must be given slowly-no more than 10-20 mmol per hour-and always with continuous ECG monitoring. Rushing it can stop your heart. But replacement alone isn’t enough. You need to stop the leak. That’s where potassium-sparing diuretics come in. Spironolactone (12.5-25 mg daily) and eplerenone (25 mg daily) are now standard for most heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). These drugs block aldosterone, the hormone that tells your kidneys to dump potassium. They don’t just help with potassium-they cut mortality by 25-30% in clinical trials.SGLT2 Inhibitors: The Game-Changer You Might Not Know About

In the last five years, a new class of drugs has quietly changed heart failure management: SGLT2 inhibitors. Originally developed for diabetes, drugs like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin have been shown to reduce hospitalizations and death in heart failure-even in patients without diabetes. How? They make you pee out sugar and salt, but not potassium. In fact, they reduce total diuretic needs by 20-30%. That means less potassium loss overall. They also lower blood pressure, reduce fluid overload, and improve heart muscle function-all without triggering hypokalemia. The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guidelines now recommend them for nearly all heart failure patients, regardless of diabetes status. If you’re still on high-dose furosemide and your potassium keeps dropping, ask your doctor if adding an SGLT2 inhibitor might let you reduce your diuretic dose. It’s not just about the pill-it’s about resetting your whole treatment plan.When to Monitor and How Often

Checking potassium isn’t a one-time thing. It’s part of ongoing care. Here’s the real-world schedule that works:- When starting or changing a diuretic: check potassium in 3-7 days

- When adding an MRA or SGLT2 inhibitor: check again in 1-2 weeks

- Once stable: monthly checks are enough

- If you’re hospitalized for worsening heart failure: check every 1-3 days

Diet and Sodium: The Hidden Trap

You’ve probably been told to cut salt. That’s good advice-but it’s not simple. When you eat less sodium, your body releases more aldosterone to hold onto what’s left. That same hormone makes your kidneys dump more potassium. So, if you’re on a very low-sodium diet (under 2 grams per day) and still on diuretics, you might be setting yourself up for hypokalemia. The sweet spot? Aim for 2-3 grams of sodium per day-not zero. That’s about 1 teaspoon of salt spread across meals. Don’t obsess over every pinch. Focus on avoiding processed foods, canned soups, and fast food. Fresh vegetables, lean meats, and whole grains are naturally low in sodium and high in potassium. Bananas, spinach, potatoes, beans, and yogurt can help naturally boost your levels without supplements.What to Avoid

Some things make hypokalemia worse-and they’re easier to avoid than you think:- Excessive caffeine or alcohol: Both can increase urine output and potassium loss.

- Laxative abuse: Often hidden in patients with chronic constipation or eating disorders. Ask your doctor if this could be a factor.

- Combining multiple diuretics: Adding metolazone to furosemide can help with stubborn fluid retention-but it also increases potassium loss. Only do this under close supervision.

- Skipping doses: Irregular diuretic use leads to unpredictable potassium swings. Take your meds on time, even if you feel fine.

What’s Next: Personalized Care

Heart failure isn’t one-size-fits-all. Your kidney function, age, other medications, and how much fluid you’re holding all change how diuretics affect you. Newer approaches use biomarkers like BNP (a heart stress hormone) and eGFR (kidney filter rate) to guide dosing. Studies suggest that tailoring diuretic doses based on these markers can reduce hypokalemia by 15-20% compared to standard dosing. The future is in smarter, gentler diuretics-like extended-release formulations that give steady effects over 24 hours instead of sharp spikes and crashes. These aren’t widely available yet, but they’re coming. In the meantime, the best strategy is simple: monitor, adjust, and add the right medications.Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get enough potassium from food alone if I’m on diuretics?

Food can help, but it’s rarely enough on its own. A banana has about 400 mg of potassium (10 mmol), and you need 40-80 mmol daily to correct a deficiency. That’s 4-8 bananas a day-plus spinach, beans, potatoes, and yogurt. Most people can’t eat that much, especially with heart failure diets that limit fluids. Oral supplements are usually necessary. Always check with your doctor before increasing potassium-rich foods if you’re also on ACE inhibitors or MRAs, as this can raise potassium too high.

Why does my doctor keep changing my diuretic dose?

Heart failure is dynamic. Your fluid status changes daily based on diet, activity, infections, or even weather. If you’re gaining weight or swelling up, your doctor may increase your diuretic. If you’re losing too much potassium or your kidneys start to struggle, they’ll reduce it. It’s not random-it’s a balancing act. Frequent adjustments are normal and often necessary to stay safe.

Is it safe to take potassium supplements with my other heart medications?

It depends. Potassium supplements can be dangerous if you’re taking ACE inhibitors, ARBs, MRAs, or NSAIDs, because these drugs can also raise potassium. Taking extra potassium with them can push your levels above 5.5 mmol/L, which can cause cardiac arrest. Always get your potassium checked before starting supplements. Never self-prescribe. Your doctor will decide the right combination based on your blood tests and overall health.

What if my potassium keeps dropping even with supplements?

If potassium stays low despite supplements and an MRA, your doctor may consider reducing your loop diuretic dose and adding a thiazide like metolazone at a low dose (2.5 mg) to boost diuresis without needing higher doses of furosemide. Another option is switching from furosemide to torsemide, which has a longer, more stable effect and may cause fewer potassium swings. Sometimes, an SGLT2 inhibitor is the missing piece-it reduces fluid overload without draining potassium.

Can hypokalemia be reversed completely?

Yes, if caught early. Most patients recover fully once potassium is restored and the underlying cause is addressed. But if low potassium persists for months, it can damage heart muscle cells and make arrhythmias more likely-even after levels normalize. That’s why early detection and consistent monitoring are critical. Don’t ignore small dips in potassium. Treat them like warning signs, not minor lab quirks.