Congestion pricing promises faster commutes, cleaner air, and new funding for transit-but it also sparks fierce debate.

When city streets grind to a standstill, Congestion pricing is a demand‑based fee that drivers pay to enter high‑traffic zones during peak hours aims to restore flow and shift travel behavior.

What does congestion pricing actually mean?

Urban mobility covers how people move through cities using all modes of transport is a moving target. Traffic congestion refers to the slowdown of vehicles when demand exceeds road capacity creates wasted time, fuel, and emissions. By charging a variable fee for entering a congested area, authorities create a price signal that encourages drivers to travel at off‑peak times, switch routes, or consider alternative modes.

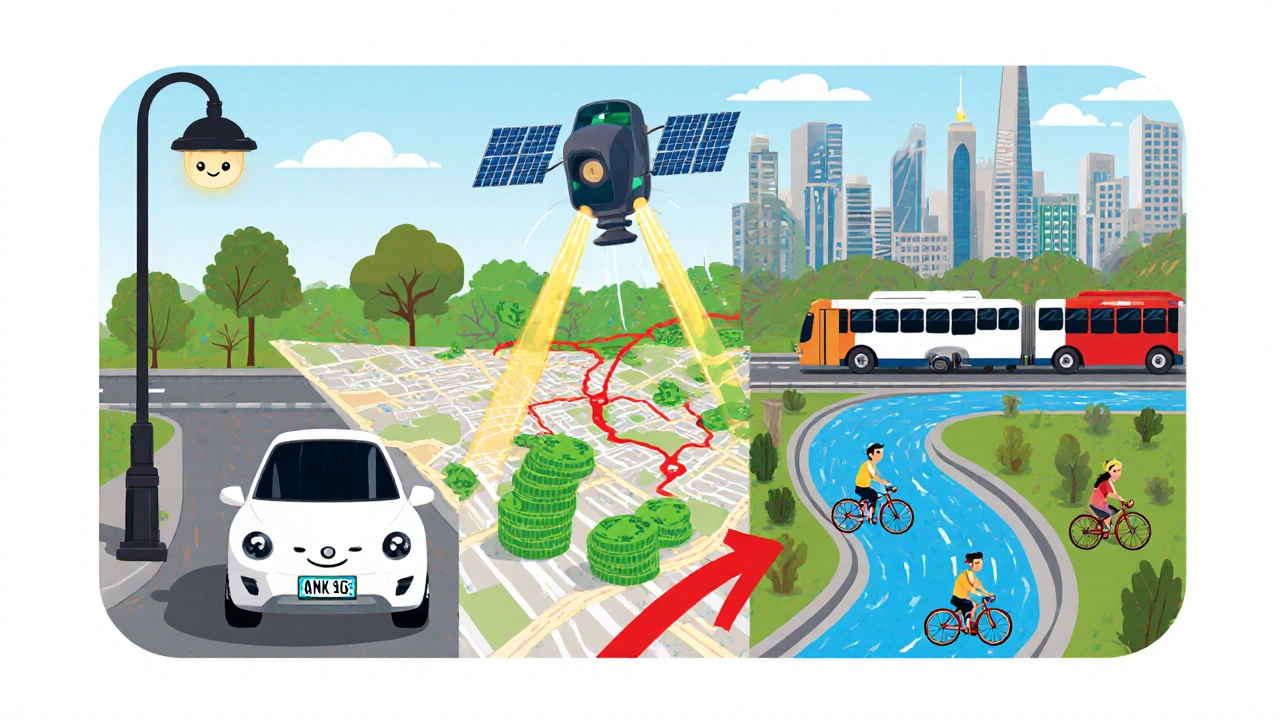

How does the system work?

Most schemes rely on automatic number‑plate recognition (ANPR) cameras or GPS‑based tolling. Drivers are billed either daily, weekly, or per‑trip. The fee structure can be:

- Flat rate for any entry during peak hours.

- Dynamic pricing that rises as traffic density climbs.

- Variable rates based on vehicle type-heavy trucks often pay more.

Revenue is usually deposited into a dedicated fund that supports Public transit bus, rail, and bike‑share services upgrades, road maintenance, or other mobility projects.

Key benefits (the pros)

- Emissions reduction Lower vehicle miles traveled translate into fewer greenhouse gases and pollutants, improving air quality.

- Travel times shrink as traffic flow smooths out, saving commuters up to 30% of their usual time.

- Revenue can finance Public transit funding new subway lines, bus rapid transit, and cycling infrastructure, creating a virtuous cycle of modal shift.

- Reduced congestion encourages economic productivity-businesses benefit from faster deliveries and lower logistics costs.

- Data collected by the system provides insights for future Smart city initiatives that use technology to improve urban living planning.

Common drawbacks (the cons)

- Equity concerns Low‑income drivers may bear a disproportionate share of costs if alternatives are unavailable or unaffordable.

- Implementation costs are high; installing cameras, billing systems, and enforcement staff can run into hundreds of millions.

- Drivers may divert to side streets, shifting congestion to residential neighborhoods.

- Political resistance is strong; motorists often view the fee as a tax rather than a service.

- Privacy advocates worry about continuous vehicle tracking and data security.

Real‑world examples

Several cities have trialed or permanently adopted congestion pricing, offering valuable lessons.

- London implemented the world’s first large‑scale congestion charge in 2003, cutting traffic by 15% and raising £1.5billion for transit upgrades.

- Singapore uses an electronic road pricing (ERP) system that adjusts rates every few minutes based on real‑time traffic flow.

- Stockholm ran a trial in 2006, saw a 20% drop in traffic, and later made the scheme permanent, funding new metro lines.

- Oslo combined a city‑center toll with a strong public‑transport network, achieving a 25% reduction in car trips.

Revenue allocation and equity

How cities spend the money often determines public acceptance. The most successful schemes earmark funds for:

- Subsidized Public transit fares making alternatives cheaper for low‑income riders.

- Improved cycling lanes and pedestrian zones, giving non‑drivers safer routes.

- Technology upgrades like real‑time traffic dashboards that benefit all commuters.

To address equity, some programs offer discount cards for residents on low incomes or reinvest a portion of the revenue into community projects in affected neighborhoods.

Implementation hurdles and best practices

Getting a congestion pricing scheme off the ground requires careful planning:

- Conduct a robust traffic model to predict demand shifts and identify optimal pricing zones.

- Engage stakeholders early-business owners, residents, and advocacy groups-to build trust.

- Set clear, transparent goals (e.g., reduce peak traffic by 20% within two years).

- Design a tiered fee structure that balances effectiveness with affordability.

- Invest in high‑quality enforcement technology to minimize evasion.

- Publish revenue reports regularly to demonstrate where funds are going.

Pros vs. Cons at a glance

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Reduces traffic volume and travel time | High upfront infrastructure cost |

| Lowers emissions and improves air quality | Potential equity burden on low‑income drivers |

| Generates stable revenue for transit upgrades | May shift congestion to side streets |

| Encourages modal shift to public transport, cycling, walking | Privacy concerns over vehicle tracking |

| Provides data for smarter city planning | Political opposition and public perception issues |

Frequently Asked Questions

How is the fee calculated?

Fees can be a flat rate, a time‑of‑day charge, or a dynamic price that rises with traffic density. Some cities also differentiate by vehicle type.

Will congestion pricing really reduce traffic?

Studies from London, Singapore, and Stockholm show traffic reductions of 15‑20% during peak periods when pricing is properly calibrated.

What happens to the money collected?

Most jurisdictions earmark revenue for public‑transport improvements, road maintenance, and active‑transport infrastructure. Transparency reports are essential for public trust.

Is congestion pricing fair to low‑income commuters?

Equity measures-such as discounted passes, revenue‑sharing with affected neighborhoods, or affordable transit alternatives-can offset disproportionate impacts.

Can technology make enforcement easier?

ANPR cameras, RFID tags, and GPS‑based tolling automate detection and billing, reducing the need for manual patrols and lowering evasion rates.